A new and lightweight plow type

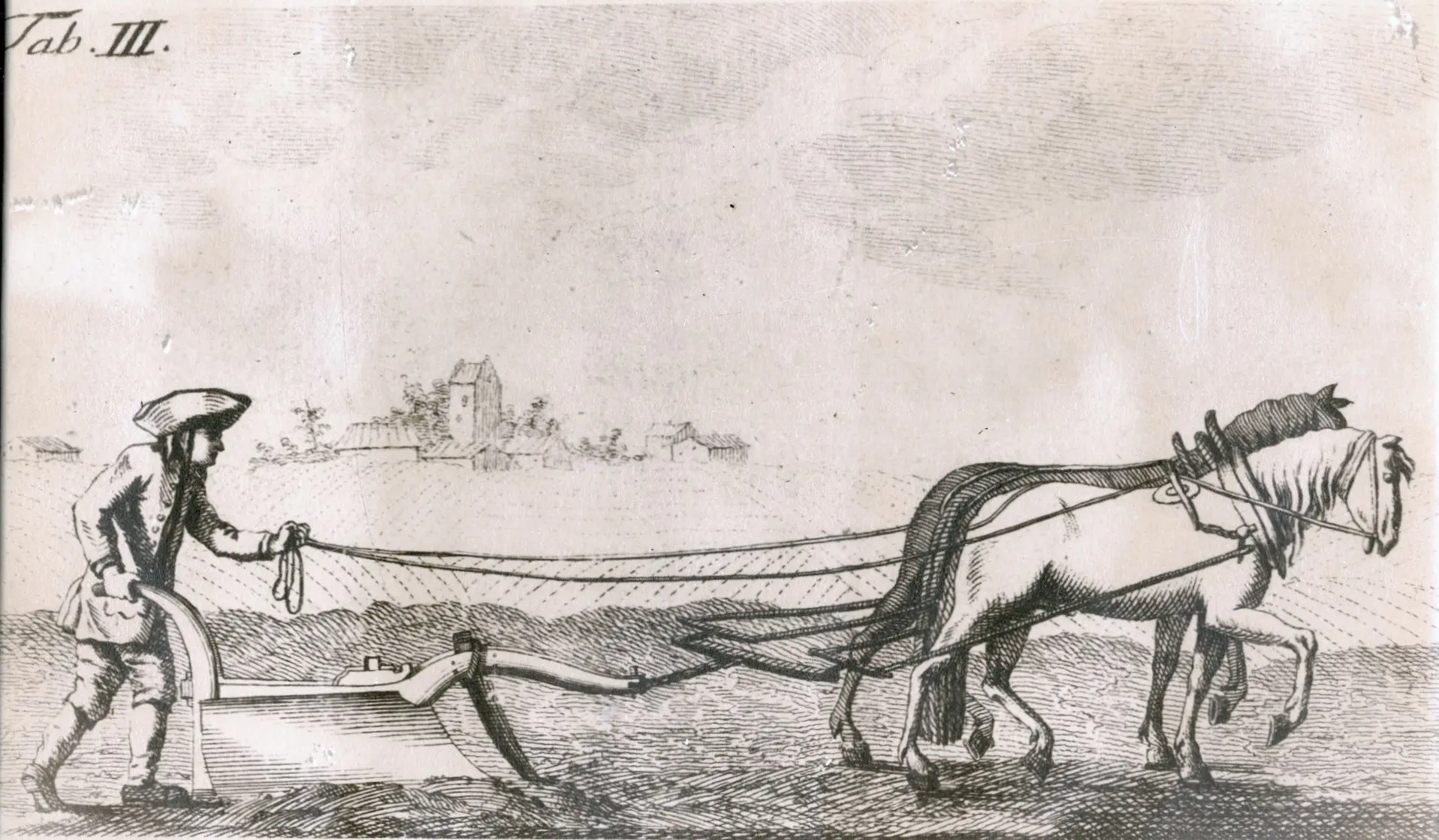

In the 18th century in Holland and Great Britain, clever and resourceful people experimented with new plough models that could advantageously replace the traditional wheel plough that had dominated field work for centuries. The result was a much smaller and therefore significantly lighter triangular plough. Whereas the wheel plough was mostly made of wood, the new plough was primarily made of iron. Nevertheless, it was so light that it did not need to be supported by a wheel. It could also be pulled by just two horses and manoeuvred by a single man. The new plough type became known as a swing plough.

The invention made heavy ploughing work cheaper, easier and more time-saving in every way than before. Since the swing plough did not require as many draft animals as the wheel plough, it also meant that horsepower could be freed up for other tasks. In addition, with the swing plough requiring only two horses, smaller areas were also needed for growing oats and other horse feed. Fewer horses also meant that it was no longer necessary to keep large areas free for the horses' summer grazing. The freed up fields could be used for growing grain and other useful crops.

“Unwillingness to use a new tool”

It was the Royal Danish Agricultural Society, which was interested in everything that improved field work, that seriously worked for the introduction of the swing plough in Denmark. As early as 1770, a plough trial was arranged, where Norwegian-made swing ploughs were allowed to try their hand at the traditional wheel plough. During the same period, the society also purchased several foreign swing ploughs for use in future demonstration ploughings. In the 1820s-1840s, the Agricultural Society also held competitive ploughings with the swing plough on both Zealand and Jutland. The intention was to “overcome the unwillingness of servants to use a new tool and awaken their sense of good ploughing by rewarding the most skilled ploughmen”. If one could handle the modern swing plough, a handsome sum of money, honour and fame awaited them.

Despite information campaigns, prizes and demonstrations of the swing plough's excellence, many Danish farmers were more than sceptical of the new plough. Firstly, they did not believe that the swing plough cut as deeply into the soil as the wheel plough. Secondly, it required a certain amount of experience to control the swing plough. A astonished farmer from Funen also described the swing plough as "completely beyond all reason", while another farmer concluded that one had to run after the swing plough to be able to keep up at all. It was therefore not without reason that the anonymous author of the practical handbook "Lommebog for Bønder" in 1792 complained that the farmers of North Jutland would not know about the swing ploughs, but ploughed with wheel ploughs as they used to. In Kragelund parish in central Jutland, the Landhusholdningsselskabet therefore chose a completely different strategy in the 1830s when they wanted to demonstrate the qualities of the swing plough. The society simply gave the parish bailiff a free swing plough. Then the local official could quite literally lead by example.

It was not until the 1850s that the swing plough really began to find favour with the farmers. This was not least due to the fact that Danish factories and iron foundries could now produce swing ploughs and the associated spare parts of good quality themselves. This was done at significantly cheaper prices than the swing ploughs that previously had to be imported at high prices from foreign manufacturers.