The first wave of mechanization

Mechanization is not a completely new phenomenon in Danish agriculture. Already in the late 1800s, new machines such as seeders, fertilizer spreaders, harvesters and threshing machines began to be introduced. This caused a great stir because people could now get help with many of the toughest tasks. Some of the machines came especially from the USA, where development was rapid. In Denmark, the new machines were widespread in the first half of the 1900s, when Danish manufacturers of agricultural machinery and tools also entered the field. Hand tools and manual labor were now partly replaced by mechanical solutions and machines. The machines replaced previous tools such as scythes for harvesting and flails for threshing.

Agriculture after World War II

Despite the first wave of mechanization, Danish agriculture after World War II was still characterized by manual labor and hand tools. Many tasks in the field and barn were still physically demanding. Only very few farms had introduced milking machines. Milking work was grueling and the more than 5 billion kg of milk that was produced annually – about the same as today – was still milked by hand.

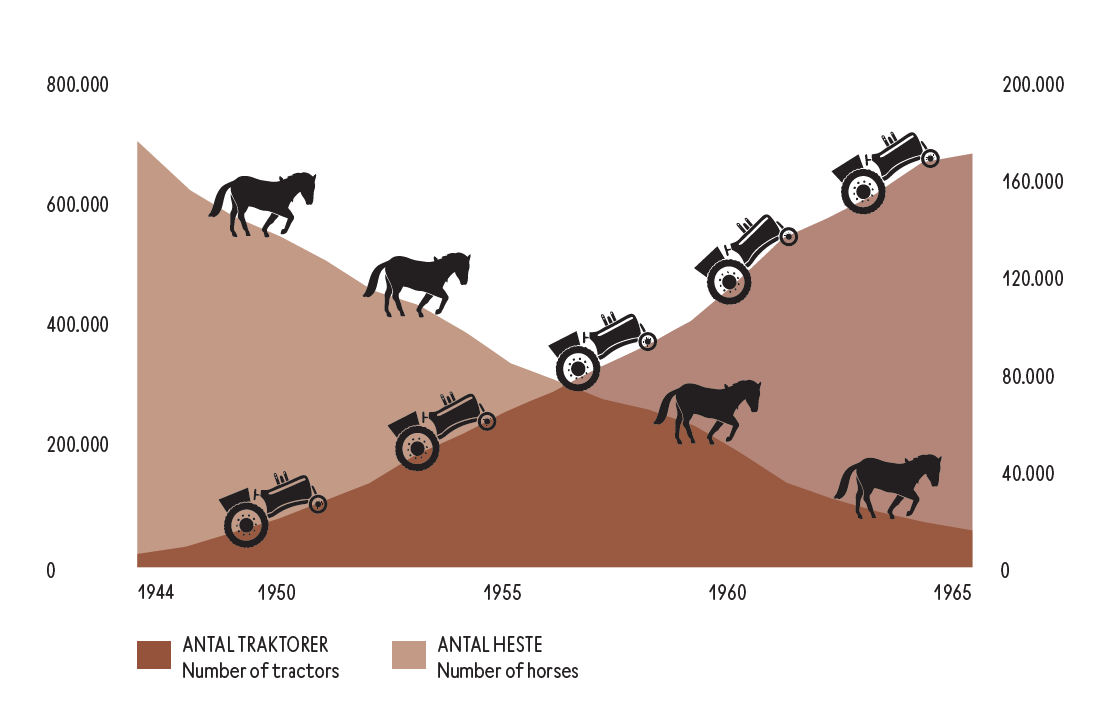

Just like the milking machine, you had to look far and wide for tractors in Danish agriculture. Only a few of the largest farms and manors had acquired tractors in the interwar years, such as a Marris-Harris Wallis or a Fordson N. The tools, the machines in the field and the work wagons were therefore almost everywhere pulled by horses. Just after the war, there were over 600,000 horses in Danish agriculture, which together with the farmers and the many helpers on the over 200,000 agricultural properties formed an ancient working community between animals and humans.

The second wave of mechanization

But the old working community – and agriculture as a whole – faced a significant upheaval in the following decades. It began with milking machines, and during the 1950s almost all farms had milking systems installed in the cowshed. The old hand milking was replaced by suction cups, vacuum pumps and pipes.

The tractor's entry into Danish agriculture was almost as rapid. Especially the English-made "little grey" Ferguson became popular in Danish agriculture in the 1950s. The number of tractors increased from just under 5,000 in 1944 to over 160,000 in 1965. This meant that almost all farms now used tractors as traction instead of horses. During the same period, more than half a million horses disappeared from agriculture.

The arrival of the tractor emphasizes the special nature of the second wave of mechanization after World War II. Unlike the earlier machines, which were often pulled by horses, the new mechanization was based on an increased consumption of fossil fuels. This meant that the new machines were far more powerful than before.

The tractor became an icon of the new era that agriculture was entering, especially in the 1950s. The extra horsepower made it possible to pull larger and heavier implements. The tractors were also equipped with hydraulic three-point linkages, where implements and machines could be mounted. With the three-point linkage, for example, larger ploughs or field sprayers could be easily raised and lowered via a mechanism and thus handled much easier.

At least as important as the three-point linkage was the power take-off, where kinetic energy from the tractor engine was transferred to the machines by means of a rotating shaft. The mechanism in seed drills, fertilizer spreaders, syringes and countless other tools could now run stably and at full power.

New machines and technical installations

The green harvester was one of the new machines where the power take-off particularly came into its own. The grueling work of especially topping beets was now replaced by a machine that toped the beets at the same time, chopped the tops into pieces and blew them directly into a wagon. The first green harvesters came in the late 1950s and became common during the following decade.

The harvesting of grain crops was also made significantly more efficient. The new combines, which entered Danish agriculture in the 1960s, replaced the previous self-binders and threshing machines. The work that had previously been done by two separate machines was now combined in one giant machine.

After the arrival of milking machines, a large number of other new machines and technical installations were also introduced to make work in the stables easier. This included, for example, manure removal systems and later slatted floors and slurry channels, which made a large number of previous tasks redundant. Feeding was also mechanized with new motor-driven feed wagons and later automatic feeding systems.

The helpers disappear and the landscape changes

Mechanization thus saved labor throughout agriculture, and it was crucial in a period when helpers moved from the countryside to the cities to get better-paid jobs in the growing industrial and service sectors. The over 200,000 helpers in 1950 had been reduced to around 30,000 by 1970. The machines replaced people, which also changed life on farms and in village communities, where there were suddenly far fewer people present.

It was not only work and life on farms that changed with mechanization. The agricultural landscape also underwent a significant change during the period. When horses disappeared, large areas that were previously used for growing horse feed were freed up for other purposes. The cultivation of barley in particular progressed, which supported the growing pig production that still characterizes Danish agriculture today. In general, fields became larger so that the new machines could be utilized more optimally, and with the increasing consumption of artificial fertilizers and pesticides, the fields also became more uniform.

Specialization and structural development

The mechanization of agriculture was also closely linked to another development, namely specialization. The new mechanized technology was built in stables and on farms that increasingly specialized in either milk or pig production. Until around 1970, the vast majority of farms had both pigs and cows, but during the 1970s specialization really took hold, and in 1980 only a third of all farms still had both animal species.

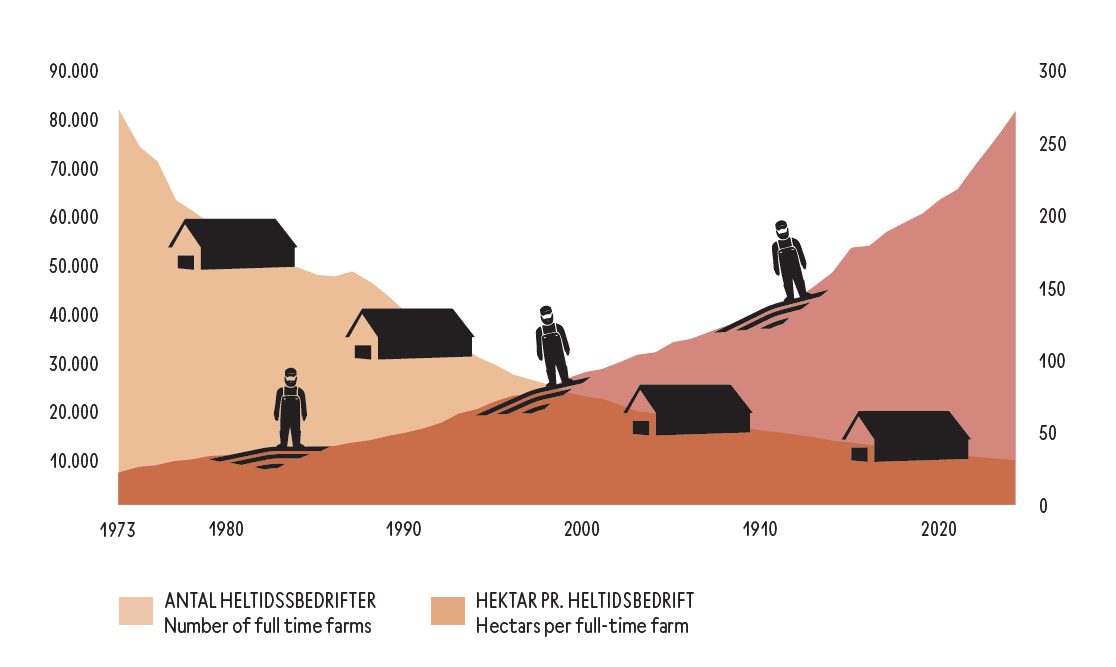

Mechanization after World War II quickly spilled over into other aspects of the great upheaval in agriculture. Mechanization and specialization led to a marked increase in agricultural productivity, which in turn led to so-called structural development. The approximately 200,000 small and medium-sized, versatile agricultural properties that existed in 1950 have today been reduced to just under 6,000 full-time farms characterized by high specialization and large-scale operation.

The extensive changes that agriculture has undergone with mechanization, specialization and structural development mean that today's fields are cultivated and animals are kept in a way that would be difficult to recognize for a farmer from 1950. In other words, agriculture has undergone a comprehensive transformation in just a few generations.