The reform period

The Reform Period is the name given to the period in Danish history in which a series of reforms reshaped Danish society and landscape forever. The Reform Period began in the 1750s. It rolled like a mighty wave across the country in the 1780s and 1790s and can be largely considered to have ended in the first decades of the 19th century.

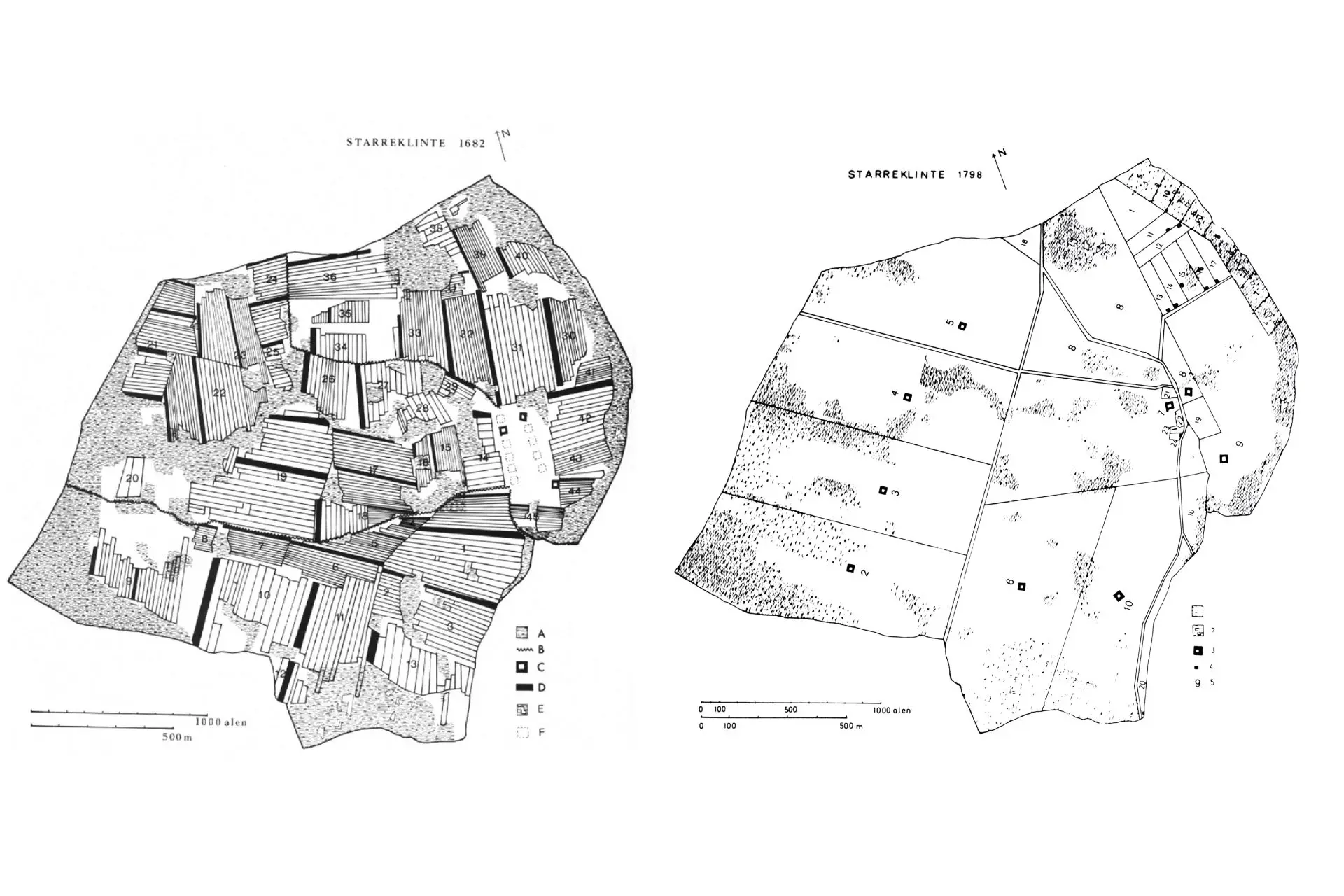

Since the 13th century, when population growth, warmer weather and better harvest yields had brought new land under the plough, the driving force and core of Danish agriculture had been characterised by the village community.

The community is due to the fact that the farmers of each village had shared the village's cultivated land among themselves in solidarity. Each farm had received its fair share of both the rich and the poor soil, the cultivated land was spread in a series of long strips over a larger area.

A necessary community

To avoid chaos, the farmers had to agree on the right times to sow and harvest. Fencing the village fields and deciding which crops to grow where were also imperatively discussed and carried out together.

The village community was therefore not only a farming community, but also a social and legal community. Rural life in 18th-century Denmark therefore had little in common with today's intensively exploited landscape with heavily trafficked motorways, enormous cornfields, hedgerows and high-voltage power lines. On the contrary, it consisted of a large, colourful patchwork with relatively few cultivated fields and desolate stretches of heathland, wildly growing scrub, large boulders, bogs, waterholes, wilderness and wet meadows where wolves and wild boars roamed. In addition, there were the so-called "overgrazing" - large communal and weed-infested fields where the farmers' lean cattle gnawed the grass down to the very last straw every year.

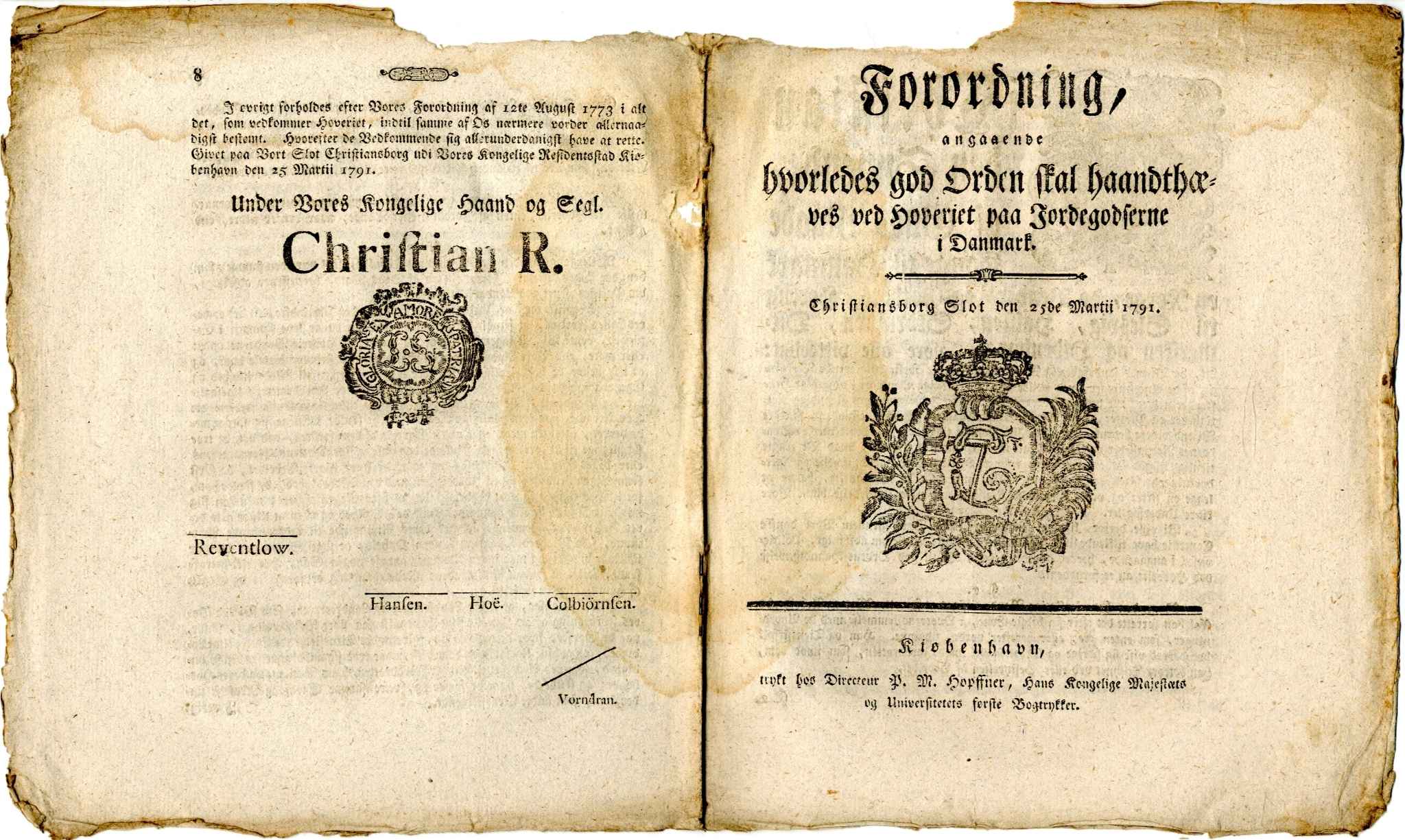

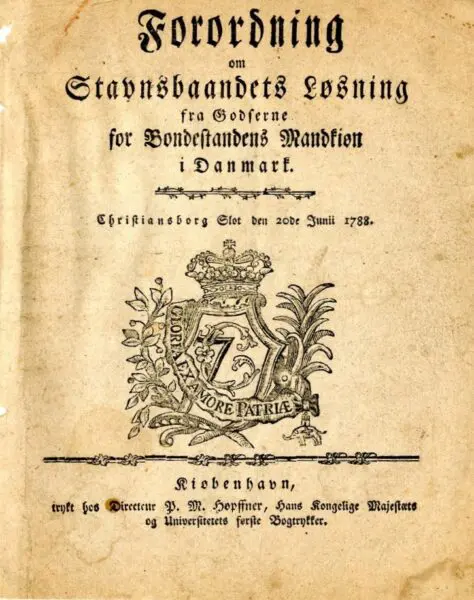

The stem band is inserted.

The Reform Period was such a radical break with the past, for two reasons. Firstly, it meant the end of the history of the rural community. Secondly, a landscape was created where almost nothing was left untouched by human hands. With the Reform Period, wild nature was tamed once and for all and forced into retreat. Since then, there has been no turning back. It was also of crucial importance that over 80% of Denmark's population in the 1750s lived in the countryside as tenant farmers and now had to adapt to a completely new life.

As a tenant farmer, you had the right to use, but not the right to own, your farm and land. On the other hand, these belonged to the landlord, just as every tenant farmer was financially, administratively and personally subject to the control of their landlord. 18th-century Denmark has been characterized as a “landowner state” with good reason. The central and local administration was not yet so well-functioning, so a number of tasks were left to the landlords.

It was the landowners who collected the taxes and duties that the king was entitled to, just as it was the landowners who were responsible for the conscription of soldiers from among the young peasant sons who lived on their land. It was precisely the fear of many long years of brutal service as a soldier that meant that many peasants chose to run away. This then fell back on the landowners' need for labor. To put an end to emigration from the countryside, Christian VI introduced the parish bond in 1733, which prohibited peasants from moving from their home parish. In this way, the king and the landowners killed two birds with one stone. The required labor force as well as the potential cannon fodder were now tied to the land.

Hoover

Apart from the annual land fee or farm rent, if you will, which the tenant farmers had to pay to the landlord in the form of money, grain or other in-kind, when they took over their tenement they also had to commit to providing manual labor on the manor. This was the so-called “servitude”. Of course, every manor had servants who took care of the daily and regular tasks inside and outside, but when it came to agriculture, many more hands were required.

There was no specific legislation regulating which and how many working days and tasks a landowner could put his tenant farmers to work. The workload depended entirely on the agreement made between the landowner and the individual farmer. This happened when the farmer was given one of the manor's farms in tenancy. During the sowing and harvesting seasons, the farmers had to provide horses, ploughs, harrows, scythes, rakes and other field tools. At other times, the work of the tenant farmers could involve maintaining fences and enclosures or transporting grain, dung, peat, heather and other fuel to and from the manor. It could also involve cleaning the cattle's watering places, mixing manure, spreading manure, cleaning grain, threshing grain, cutting peat, forestry, chopping wood or collecting stones on the manor's fields. Repairs to and cleaning of the manor itself and its houses could also occur.

Trevangsbrug

Rising grain prices motivated many landowners from the 1750s to increase the burden of the lordship so that they could reap the fruits of the good times. It was especially bad on Zealand and Lolland-Falster. Firstly, the soil here was particularly fertile and therefore gave extra returns. Secondly, it was often Copenhagen businessmen who had acquired a manor house and now wanted to push the labor of their tenant farmers to the limit.

On Funen, Zealand, Lolland-Falster and the surrounding islands, the villages' work with the land was organised in the so-called "trevangsbrug", where the common land was divided into three large fields/vanges. The three-vanges farm functioned in such a way that the crops alternated between the three vanges. As a rule, barley was sown in the first vange in the spring and rye in the second vange in the winter, while the third vange lay uncultivated and was instead used as a common grazing area for the village's cattle. The advantage of the three-vanges farm was that the crops were less vulnerable to crop failure and bad weather. If the spring barley failed, the winter rye was still available to fall back on. The problem was that the three-vanges farm gave the best harvest yield in fertile soil, which was not an available resource everywhere in Denmark. The cultivation method therefore also entailed a great risk of the soil being exhausted. Already in the Middle Ages, the solution had been to let livestock graze on the harvested and uncultivated fields so that their manure could benefit the soil.

Self-owned

Self-ownership meant in concrete terms that a tenant farmer now bought the farm and agricultural land that he had previously held in trust from his landlord. Where the farmer had previously been a tenant, he had now become the owner and could dispose of his farm and fields himself.

In contrast to the abolition of the Stavnsbåndet, the transition to freehold was not a new law that put an end to the feudal system with a stroke of the pen. On the contrary, the king and his officials were on the defensive when it came to promoting freehold. The Copenhagen government offices were certainly of the clear opinion that farmers who owned their own land would prove to be far more useful and productive than feudal farmers. But it was still impossible to force the landowners to sell their farms and fields to the farmers. For the same reason, the transition from feudal to freehold was a lengthy process that was not finally completed until the 1850s. An example of a relatively late transition from feudal farmers to freehold farmers can be cited as the residents of the village of Storvorde in eastern Himmerland. It was not until the 1840s that the residents here had saved enough money to be able to buy the farms from the landowner at the nearby Klarupgaard.

On the contrary, these were local agreements that were entirely dependent on local conditions and were concluded between the individual landowner and his tenant farmers. The motivation for both parties to buy and sell must be found in the growing European demand for Danish grain. It could well be profitable for a tenant farmer to buy his own land and dispose of the crops himself.

The replacement

The government tried in various ways to encourage landowners and farmers to sell and buy. The landowners were promised that the sale of their farms would not affect the tax exemption that was inextricably linked to the size of their property. In return, farmers who were eager to buy were given the opportunity to borrow money for the purchase price at favorable interest rates through various public money banks.

The exchange will be defined here as the abolition of the land and cultivation community. This meant that the individual farmer's fields, which had previously been spread over a larger area, were now exchanged/collected into a large and continuous piece. The exchanges began in the 1750s and can be described as completed around 1805. An exchange could take place solely on the initiative of the landowner. In fact, it did not have to be a decision that his tenant farmers had any influence on in any way. The motivation for even embarking on such a project was the desire for a more efficient use of the agricultural land. The royal power was interested in the expanded taxation base of the agricultural land that the exchanges would result in.

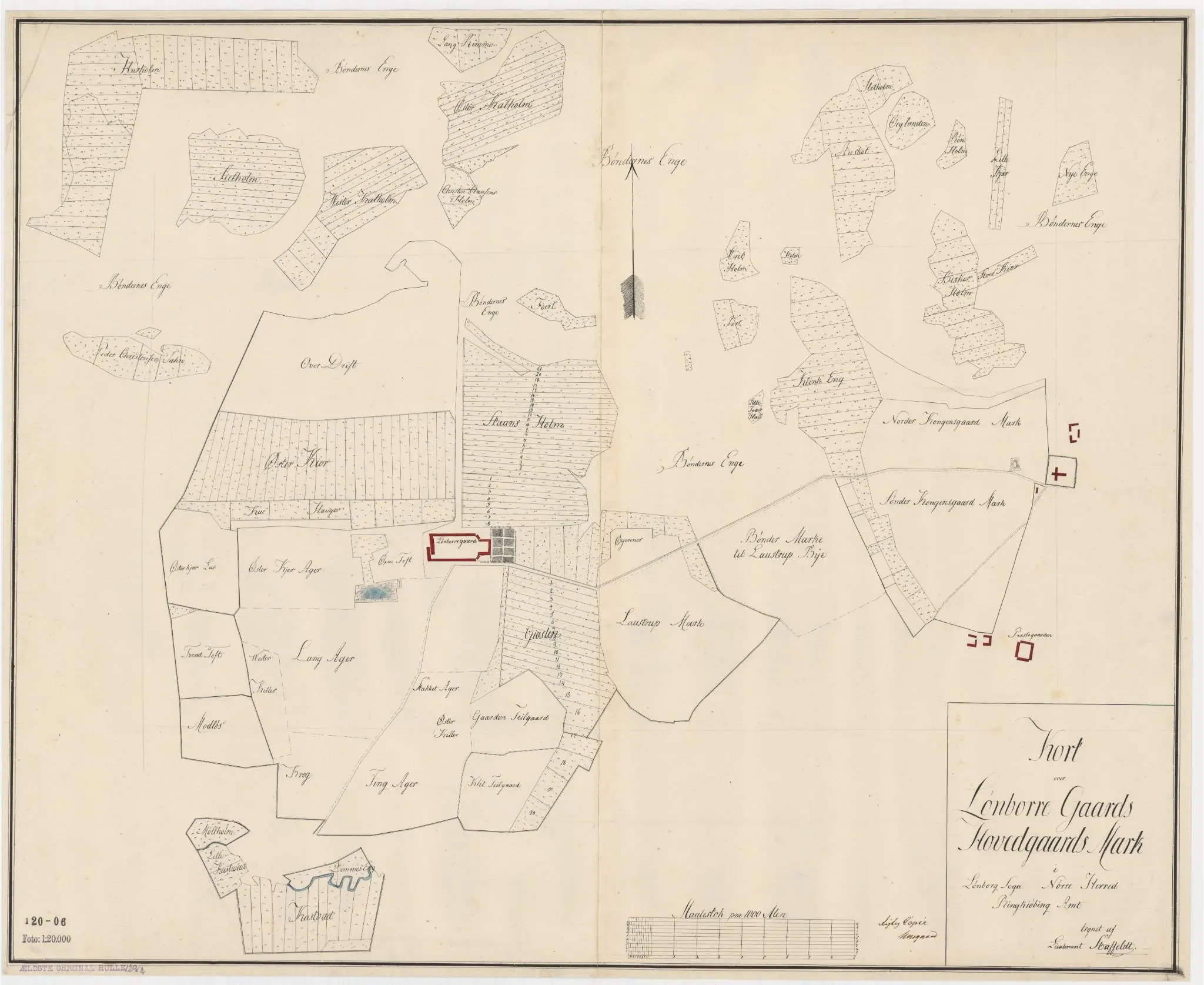

Lønborggaard's replacement

An example of how such a replacement took place is the Lønborggaard manor house at Ringkøbing Fjord in West Jutland. Lønborggaard's cornfields, meadows, heathlands and peat bogs had for many years been spread over far too many and far too small areas. In 1792, Lønborggaard's owner, Captain Niels Jermin, decided that it would be more profitable to replace the manor's land and collect it into larger and more productive units. Lønborggaard's eight villages with their 60 farms and 30 houses were clustered together on the edge of the manor land. It would therefore also make good sense for Jermin to let some families move out into the fields.

As planned, so it was done. Jermin's first step was to have his land surveyed and divided into equal fields. For this work, he received assistance from the surveyors in the Land Administration Commission, which the government had established to speed up the exchange process. After Lønborgaard's land had been surveyed and drawn on new maps, Jermin's tenant farmers were called to an information meeting. Here they were asked if they had any objections to having their land collected? Jermin could await the answers with peace of mind. When it came to exchanging the land, the decision-making authority lay entirely with the landowners. It was usually the landowner, or alternatively the local parish priest and perhaps a few farmers who were lucky enough to have their own farm and land. At Lønborggaard, Jermin was the only landowner. Even though his tenant farmers might not have liked the idea of moving, there was no point in complaining. The decision had been made in advance, and the next stage of the replacement could now be addressed.

Location determined by dice roll

According to the surveyors' measurements and the Land Administration Commission's assessment, it would be appropriate to move a total of 18 farms from the eight villages. Jermin was in favor of this proposal, and the landowner also sketched a plan for how he imagined the 18 newly built farms of the tenant farmers with farmhouses, outbuildings and stables would look.

The next step was to find out which of Jermin's tenants would move. The tenants from each village were now called to the manor, because who would move? In the village of Bølle, it was about eight farms. Here the decision was made by two rounds of dice rolls. In the first round, the three farmers who got the highest number of points on the dice had to move the farms to the west. The others, on the other hand, had to settle to the south. In the next round, the dice were then rolled to determine the mutual location of the eight farms. However, the moving process was not always easy. In Volstrup, three tenants refused to move for very different reasons. One wanted to roll dice with his neighbor to decide which of the two should move, while the other thought that his new land was too poor compared to the others. Finally, there was the third tenant farmer, who, perhaps sensibly enough, wanted to look at his land before deciding to move. All complaints came from farmers who were tenants under Lønborggård. Since the farmers had no say in the process, the landowner could calmly ignore all the complaints. The replacement of Lønborggård's farmland was a reality. The episode in Volstrup, however, shows that not all tenants were equally receptive to progress.

Moving the farm stone by stone

Once the decision to replace had been made, the great and difficult work of moving the individual farms' houses, stables and barns began. We do not know the actual moving process for the tenant farmers of Lønborggård. However, we know from other replacement processes that the condition of the farms played a role. It was very sensible to prefer to demolish the villages' old and dilapidated farms to the more well-maintained ones. Then, in connection with the moving of the old ones, the required repairs could be made, any rotten wooden posts could be replaced and thatched roofs could be put in place. The moving of such worn-out farms also had the advantage that the usable building materials from the old farms could be used in the new ones.

In North Jutland, where wood was scarce, some tenant farmers preferred not to remove the roof, ceiling and floors of their houses. They simply stripped down the masonry, after which the buildings were loaded onto wagons with great difficulty and with the assistance of jacks and carefully driven to the new location. This not only saved building materials and workers' wages, but also time, as such a relocated farm could be in place in just 14 days. On the other hand, it could take up to a whole summer if a relocated farm had to be built from scratch.

It is important to emphasize that the replacement in Denmark did not happen overnight. Just as in the case of Lønborggaard, it was a long process, both administratively and practically, before everyone had found their rightful place. In fact, it took until 1861 before the replacement of the old village communities could be considered finally completed. The consequences of the replacement were most noticeable on Funen, Zealand and the surrounding islands, and in East Jutland, where the most people lived and where the villages were close together. In the more sparsely populated Northwest Jutland, farms were often far apart, so here the replacements felt like a less radical break with the communities of the past.